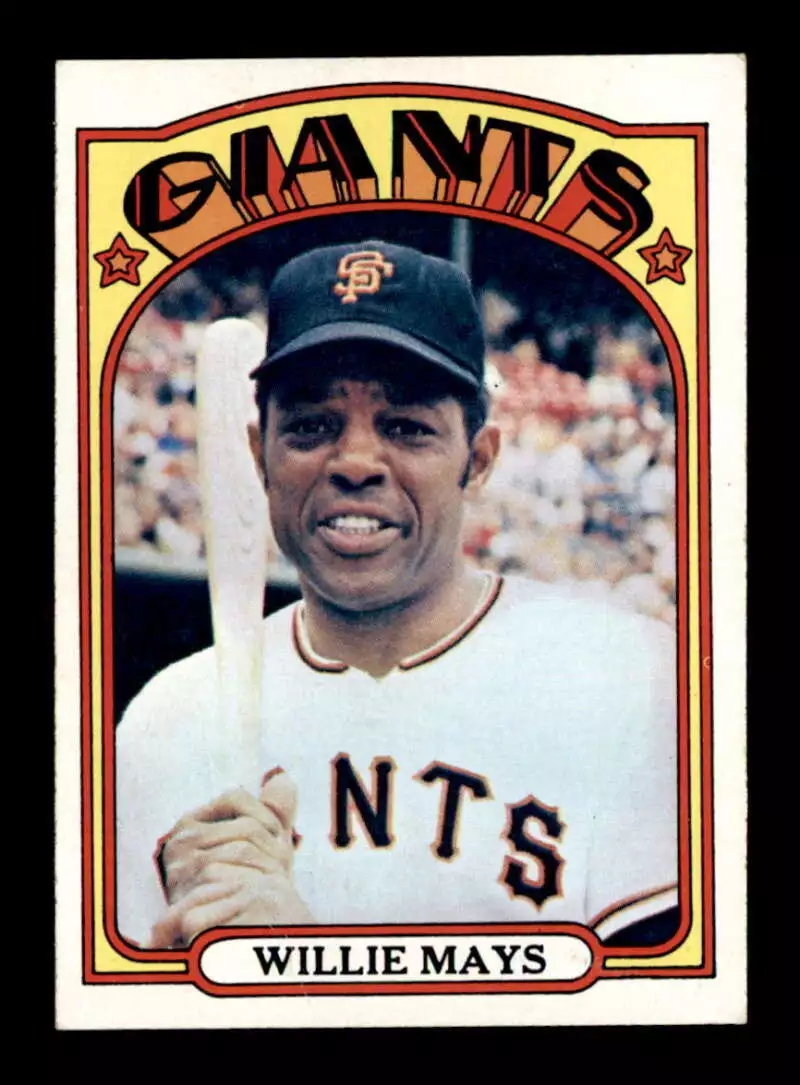

1972 Topps Willie Mays card (Topps Baseball Chewing Gum Company photo)

By Tony The Tiger Hayes

May 11, 1972 began as a vintage spring day in San Francisco 63 degrees clear skies reaching far above the just recently topped out Trans American Pyramid Building. But by early afternoon the mood in the City by the Bay had become decidedly gloomy.

Cable Car bell ringers had lost their rhythm. The Sea Lions at Fisherman Wharf stopped barking for handouts. Even the hippies in the Haight contemplated haircuts and giving up the whacky tobacco. Yes all hope had seemingly been lost as the bad news slowly crept across town like a foreboding wall of fog.

Number 24, Willie Mays the first ever big league superstar to represent a San Francisco big league team was traded by the Giants.

Though the aging long-time Giants captain, 41, had struggled at the plate to begin the ‘72 season, the trade was completed primarily to cut costs for the financially flailing Orange & Black.

An embarrassed Giants organization sent the pricy Mays, arguably the greatest player of all-time, to the New York Mets for a barely lukewarm right-handed pitching prospect named Charlie Williams and a suitcase full of rumpled $100 bills.

The previous night, in his last game as a Giant, at Park Jarre of Montreal of all places, Mays blistered a pinch-hit single off the Expos’ Mike Torrez in a 7-1 San Francisco defeat.

Suddenly, in the middle of his 22nd season as a Giant – including 15 in Bay City – Mays would no longer be representing the Orange & Black.

Though the distressing trade had been rumored for days, it still came as a gut punch to San Francisco fans and players.

“Damnit. Oh. No,” said Giants star outfielder Bobby Bonds, when informed the trade was official – no doubt speaking collectively for San Francisco players and fans alike.

The avuncular San Francisco Mayor Joe Alioto was a bit more pointedly in his comments. Alioto – a proud City native- directly blamed the Giants embattled team owner Horace Stoneham.

“There is no joy in Frisco,” Hizz Honor proclaimed with dramatic flair. “The Great Stoneham has struck out.”

Since 1958, Mays had been a San Francisco Giant when the franchise relocated from New York’s Polo Grounds.

As a west coast Giant, the Basket Catch devotee would hammer his 3,000th base hit – a baseball gold standard – and join the exclusive 500 and 600 home run clubs. He also led San Francisco to their first California National League Championship (1962) and western division crown (1971).

Mays was named 1965 NL MVP and presented with 10 consecutive Gold Glove Awards over that span (1958-68) and appeared in 14 consecutive All-Star Games for San Francisco.

The 1972 swap sent Mays back to his old stomping grounds of New York where in 1951 he was the unanimous Rookie of the Year for the New York Giants and made baseball’s signature outfield catch in the Giants World Series sweep of Cleveland in 1954 – among his other Big Apple highlights.

“I expect to play out my career in New York,” said Mays, 41, who at the time trailed only Yankees legend Babe Ruth on baseball’s all-time home run list by 68 round trippers.

The deal was announced in a joint press conference held in New York City that afternoon.

While expressing regret that Mays was leaving the club, an awkward Stoneham somberly intoned the trade was done with Mays’ best intentions in mind. The perennial All-Star was in the second-year of a $320,000 two-year contract and the Giants could no longer afford him.

“I’m sure Willie will be in good financial shape (going forward),” a forlorn Stoneham explained. “The basis on all this is on Willie’s future after he retires. I think this way is much better for Willie.”

The financially struggling Giants were at the time living a hand-to-mouth existence. Depressing Candlestick Park – just 12 years old at that point – was officially a colossal white elephant. With attendance at the chilly concrete bowl virtually nonexistent, the Giants were having trouble paying their current payroll, let alone concerning themselves with Willie’s post-playing financial interests.

The downsizing Giants – all-star pitcher Gaylord Perry and his significant contract had been shed months earlier – also had viable center field options in long-time Mays caddie Ken Henderson and promising rookie Garry Maddox.

New York – where Mays’ popularity had never waned – not only had a spot in the lineup for the aging icon, but had reserved a place for Mr. “24” as a coach and in team advertising and public relations operations when his playing days concluded.

“I think (Mays) will be very helpful this year and, years to come.” said New York executive M. Donald Grant, who assumed the balance of Mays $150,000 1972 salary. “We would like him to be out there on the field after his career is over.”

At that point in their relatively brief history, the Mets had made it a habit of adopting other New York teams former stars and stalwarts and presenting them as their own.

The 1962 expansion club’s first three managers: Casey Stengell (Yankees) Gil Hodges (Dodgers) and their current skipper Yogi Berra (Yankees) all had deep New York roots – now Mays was poised to be recycled into a Met by the Blue & Orange, who naturally nicked their color scheme from the Dodgers and Giants.

The difference was, in Mays, the Amazins’ had a legitimate on-field gate attraction or at least they prayed he was.

Following their astonishing 1969 World Series Championship three seasons earlier, the Mets had drifted into a sea of mediocrity. After two straight mid-division finishes, the 1972 Mets were more than ready to get back back in the good graces of New York’s unforgiving sports fans.

At the time of

the Mays transaction, the 1950s inspired musical “Grease” was getting boffo reviews and packing out the Broadhurst Theater on Broadway, the Mets figured if ‘50s nostalgia sold on the Great White Way it would for baseball as well.

In the charming Mays, New York would have a living and breathing- though occasionally limping – reminder of New York’s – albeit semi-mythical – Golden Age of baseball when New York ballplayers would return to their humble Brooklyn or Harlem apartments after games at the Polo Grounds or Ebbets Field and play stickball in the streets until after the street lights came on.

But the 41-year-old version of Mays the Mets were receiving would likely be more inclined to a sunset supper at the Russian Tea Room and an early turndown at his Essex House suite than breaking out a sawed off broom stick and a pink Spaldeen uptown with the kids.

After a solid – if unspectacular- season (.271, 18, 61) for upstart 1971 NL West champion Giants, the bat looked heavy in Mays hands to begin the 1972 season with San Francisco.

After a good spring camp in ‘72, Mays sat cold for two weeks before regular season games started as baseball endured it’s first ever player’s strike.

“I gained about five pounds during the strike,” Willie explained in his

final extensive press briefing as a Giant, held about a week before the trade. “I feel good in the field and on the bases, but not at the plate.”

Mays acknowledged, age was catching up with him, but he wasn’t quite ready to ride off into the sunset.

“I’ve adjusted to the fact that I’m not going to hit many home runs now. But there are

plenty of things I can do. When we have someone who is capable of going out there and doing better than I can, I’ll be the first to admit it,” Mays said, following a 2-for-3 day, in an 8-3 Candlestick Park loss, coincidentally, to the Mets (5/3/72).

The good day at the plate marked Willie’s first multi-hit game of the ‘72 campaign.

Though no one knew it at the time, the contest, played before only 4,123 fans on a wind-swept sunny Wednesday afternoon, also signaled Mays’ final home game in San Francisco.

“I think I had a pretty fair season last year,’ Mays said after the contest. “Let’s wait until this one is over before

before we evaluate. I haven’t thought about retirement yet. All I know is that will be one of the toughest decisions of my life to go into that locker and put that uniform in mothballs.”

Within days, that uniform, and the one Mays wore in Montreal were indeed put in “mothballs” and shipped to the Baseball Hall of Fame in Cooperstown, N.Y. by Giants assistant equipment manager Mike Murphy.

Willie didn’t have to wait long for a reunion with the Giants. Three days after the trade, Mays made his Mets debut- against, naturally, the Giants in New York.

Despite inclement weather, the Sunday afternoon Mothers Day crowd at Shea Stadium swelled to 35,505 – most there to lay out a Willie Welcome Matt for Mays.

Curiously Mets manager Berra positioned Mays at first base and placed him atop the New York lineup against Giants starter Sam McDowell.

Mays walked in his first at-bat (scoring on a Rusty Staub grand slam); he struck out in his second at-bat.

With the score knotted at 4-4, Mays led off the 5th vs. reliever Don Carrithers and drilled a screaming line drive over the Shea Stadium left field fence to give the Mets a 5-4 lead. The homer was the difference in the tilt.

The form wasn’t perfect – he practically stepped in bucket during the swing – but it was a no doubter. And as Willie ambled towards second base he looked up to see Giants infielder Tito Fuentes giving him a greeting.

Mays admitted after the 5-4 Mets win, that the momentous occasion left him conflicted.

“I didn’t know what the Giants were thinking. They traded me away, you know. Maybe they thought I couldn’t play anymore. (But) there was a little sentiment in my heart.

I wanted to win the ball game and yet in a way well, I had feeling for both sides, It was a strange feeling to bat against a team I played for 21 years,” Willie said. “You see the name Giants on their uniforms and you feel you should be out there with them. Look, you’ve gotta have some kinda feeling after being with one club that long.”

When Mays returned to San Francisco with the Mets in July for a Friday night contest, he was met with one of the Giants largest crowds of 1972.

Mays did not disappoint. He bopped a home run in that game as well.

Mays didn’t come close to reaching Ruth on the all-time home run list as a Met – falling 54 homers short. But he enjoyed two decent individual seasons with New York in 1972-73 and helped the Mets to the 1973 NL Championship. That club would lose the World Series in seven games to Oakland. Mays did not play particularly well in his fourth career Fall Classic – and retired as an active player after it’s conclusion at age 42.

Immediately, Willie joined the Mets coaching staff, serving under several Mets skippers through 1979.

His relationship with the Giants organization chilled during that time, but a detente’ was reached in 1983 when the Orange & Black held a day in his honor to officially retire Mays famous uniform No. 24.

By 1986, Mays was officially a Giant again when he signed a long-term personal services contract with his original team. He’s actively served in that role ever since.

This February, San Francisco officially honored the “Say Hey Kid” on 2/24/24.

Willie who lives about a 45 minute drive from the Giants current home at 24 Willie Mays Plaza will celebrate his 93rd birthday next month.

Where do you start with Mays baseball accomplishments? They are almost too unbelievable to, well, believe.

Mays, a native of Alabama, was a childhood prodigy, playing alongside his father in a men’s hardball league at age 13. By 16, Willie was an All-Star in the Negro Leagues. At age 20, in 1951, Mays made his big league debut with the Giants. After a slow start, Mays knocked a home run off the great Warren Spahn for his first hit. He finished with a .274 average, 20 long balls and ROY honors. The “Say Hey Kid”

was on deck when Bobby Thomson whacked his game-winning home run off the Dodgers Ralph Branca to send the Cinderella Giants to the ‘51 World Series.

After missing most of the next two seasons to a U.S. Army hitch, Mays returned for the 1954 season and dominated- stroking

41 home runs and 110 RBI and earning Most Valuable Player honors. The Giants swept the Indians in the ‘54 World Series and Mays made his signature over the shoulder catch of

Vic Wertz’ long drive into center field at the Polo Grounds in Game One.

The Great Giant was the first major leaguer to hit 50 home runs ind steal 20 or more bases in one season when he hit 5l homers and stole 21 bases in 1955.

The Wonderful Willie tied a major league record in 1961

when he hit four home runs in a single game at Milwaukee and on two other occasions belted three in a game.

In 1962, Mays won the NL home run crown (49) and led the Giants to their first west coast pennant, as the Orange & Black took the Yankees to a Game 7 before a heart breaking loss.

The future Hall of Famer also topped the senior circuit in long balls in 1964 (47) and 1965 (52) – winning his second MVP in the latter campaign.

He surpassed the 20-homer mark in 17 seasons -a major league mark – and at the time of the trade to New York he held records for lifetime NL home runs.

Mays’ All-Star accomplishments are fabled. He appeared 21 Mid-Summer Classics, compiling a .329 batting average in 70 at bats, winning MVP honors twice.

Mays also been a god send for sports memorabilia collectors. Some of the awesome mementos produced in his honor include signature fielder mitts, numerous bobblehead dolls and a unique statute produced by the Hartland Company in the 1950s that reproduced Willie making his signature “Basket Catch.”

Of course, there were bushels of Willie Mays baseball cards issued during and after his playing career.

Our favorite Mays related memorabilia piece happens to be the 1972 player card Topps issued for Willie.

It’s the last bubble gum card featuring Willie as an active Giants team member.

That season, Topps designed the colorful bubble gum card set in a memorable Peter Maxx inspired modern art motif with splashes of color and trippy three-dimensional fonts.

Willie’s card – no. 49 in a set of 787 – features a close-up portrait photo of Willie smiling as he stands in front of the Giants dugout at Candlestick with a bat resting on his right shoulder.

Most likely shot during the 1971 campaign when Willie would have been 40 years old – the intimate photo shows Mays’ resolve as a tried and true star ballplayer and team leader. But there is also a vulnerability etched on mature face as if he’s saying ‘hey, this isn’t as easy as it looks.”

But if anyone made it look easy … it was Willie Mays.